Explained: How Tropical Cyclones Are Named, And The Science Behind Their Formation

Each tropical cyclone basin has a rotating list of names maintained by the World Meteorological Organization. A cyclone's name is retired and replaced by another in the cases where the storm is deadly

Cyclone Biparjoy made landfall in Gujarat, India and southern Pakistan on June 15, 2023, and unleashed powerful gusts of winds. According to NASA, Biparjoy, a long-lived cyclone, had wind speeds of 129 kilometres per hour on June 14. This made Biparjoy a category 1 storm on the Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale, a 1 to 5 rating based only on the maximum sustained wind speed of a tropical cyclone. A category 1 storm produces very dangerous winds which result in some damage. Based on the Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale, category 5 storms are the most dangerous.

After spending eight days in the Arabian Sea, Biparjoy slowly moved north, and took a turn to the east on June 14.

A tropical cyclone is an intense circular storm that originates over warm tropical oceans, is characterised by low atmospheric pressure, high winds and heavy rain, and draws energy from the sea surface and maintains its strength as long as it remains over warm water.

A tropical cyclone is simply called a "cyclone" in the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea, a "severe tropical cyclone" in the western South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean, a "tropical cyclone" in the southwest Indian Ocean, a "typhoon" in the western North Pacific, and a "hurricane" in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the eastern and central North Pacific Ocean, and the North Atlantic Ocean.

How tropical cyclones are named

Each tropical cyclone basin has a rotating list of names maintained by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). A cyclone's name is retired and replaced by another in the cases where the storm is particularly deadly.

Generally, tropical cyclones are named according to rules at the regional level. Tropical cyclones receive names in alphabetical order in the Atlantic and the Southern Hemisphere, where the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean flow. For cyclones in these regions, women and men's names are alternated.

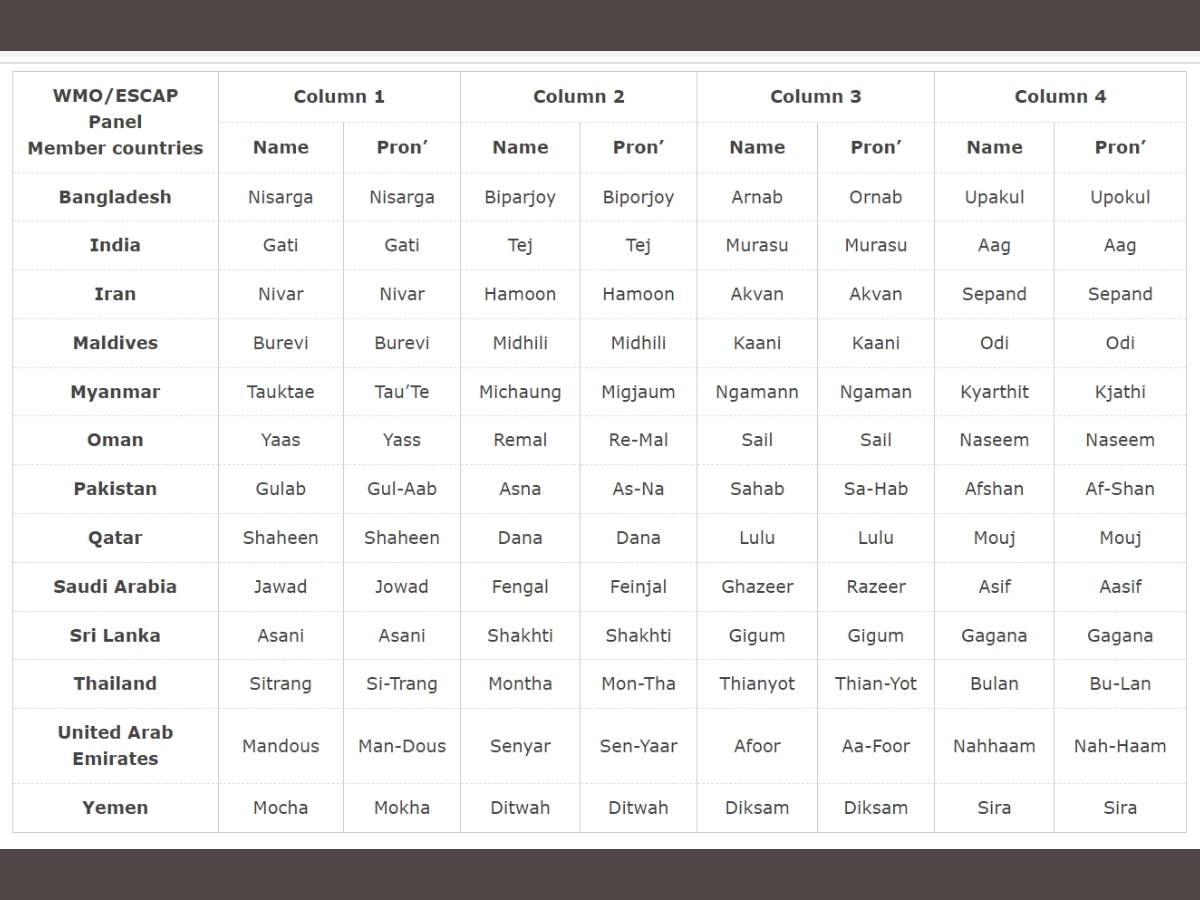

In 2000, nations in the Northern Indian ocean started using a new system for naming tropical cyclones, wherein the names are listed alphabetically country wise, and are neutral gender wise.

According to the WMO, the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) of WMO Members of a specific region propose the name list, which in turn, is approved by the respective tropical cyclone regional bodies at their annual or biennual sessions.

The five tropical cyclone regional bodies, which determine the list of tropical cyclone names for a particular basin, are ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee, where ESCAP stands for the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific; the WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones; RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee, where RA stands for Regional Association; RA IV Hurricane Committee; and RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee.

The Hurricane Committee determines a pre-designated list of hurricane names for six years separately at its annual session. For other regions, the nomenclature systems are almost the same as in the Caribbean.

The list of names to be assigned to tropical cyclones formed in the northern Indian Ocean basin, where the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal flow, was determined by the WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones at its 27th session held in 2000 in Muscat, Oman. At the meeting, they agreed to assign names to the tropical cyclones in the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea. From September 2004, the naming of tropical cyclones over the Northern Indian Ocean began. The names were provided by eight members. Five countries have joined the panel since September 2004.

The panel lists the names alphabetically country wise, and these names are used sequentially column wise.

According to the WMO, the first name started from the first row of column one, and has been continuing sequentially. It will be continued to the last row in column thirteen.

There is a rule that the names of tropical cyclones over the Northern Indian ocean will not be repeated, and once used, they will cease to be used again.

However, there is an exception. For a tropical cyclone from south China which crosses Thailand and emerged into the Bay of Bengal as a tropical cyclone, the name will not be changed.

The Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) is responsible for naming the tropical cyclones that have formed over the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea when they have reached the relevant intensity. Mocha, a name provided by Yemen, a member country of the WMO/ESCAP Panel, was a powerful tropical cyclone in the Northern Indian Ocean Basin which affected Bangladesh and Myanmar in May 2023. The cyclone which formed in the Northern Indian Ocean Basin after Mocha has been named Biparjoy, a name provided by Bangladesh, because Mocha is the last name of the first column, and Biparjoy is the first name of the second column.

How tropical cyclones are formed

A transfer of water vapour and heat from the warm ocean to the overlying air serves as the fuel for a tropical cyclone. Evaporation from the sea surface causes this transfer of water vapour and heat from the warm ocean. The warm air expands and cools as it rises. Eventually, it becomes saturated and releases latent heat through the condensation of water vapour.

This process warms and moistens the column of air in the core of the developing disturbance, according to Britannica. There is a temperature difference between the warm, rising air, and the cooler environment. This difference causes the rising air to become buoyant, which further enhances the upward movement of the warm air.

Enough heat is not available when the sea surface is too cool, as a result of which the evaporation rates are too low to provide enough fuel to the tropical cyclone. When the warm surface water layer is not deep enough, energy supplies are cut off.

The developing tropical system modifies the underlying ocean. When rain falls from the deep convective clouds, the sea surface is cooled. Also, the strong winds in the centre of the storm create turbulence. In some cases, the resulting mixing brings cool water from below the surface layer to the surface. This causes the fuel supply for the tropical system to be removed.

While the vertical motion of warm air is by itself not enough to initiate the formation of a tropical system, the flow of the warm, moist air into a pre-existing atmospheric disturbance will result in further development.

The atmospheric pressure in the centre of the disturbance is decreased because the rising air warms the core of disturbance by the release of latent heat, and direct heat transfer from the sea surface. Due to the decreasing pressure, the surface winds increase, and this, in turn, increases the vapour and heat transfer, and contributes to further rising of air. Therefore, the warming of the core and the increased surface winds reinforce each other in a positive feedback mechanism.

Related Video

Southern Rising Summit 2024: How Important is Self-Awareness? Insights from Anu Aacharya | ABP LIVE