Explorer

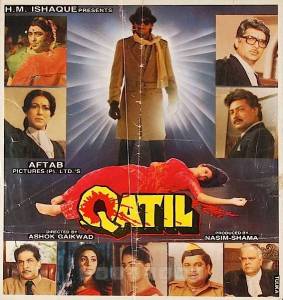

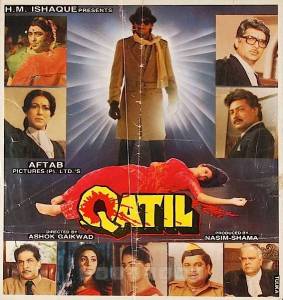

Qatil

Beyond remakes – official or otherwise, lifts – inspired or plagiarized or tributes – intended or the other variety – Hindi cinema also has the unique tradition of revisiting a popular template every once in a while. Such is the fascination for a successful formula that on most occasions rehashing it is almost like a rite of passage – Ram Aur Shyam (1967) to Seeta Aur Geeta (1972), Chaalbaaz (1989), Kishen Kanhaiya (1990) or Ganga Jumna (1961) to Deewar (1975), Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) to Raja Hindustani (1996), etc. Although cut from the same fabric, the re-examination ideally updates the formula keeping in mind the times the films are made in, but in some cases such as Qatil (1988), it doesn’t even bother with window dressing. Inspired by B.R. Chopra’s iconic Kanoon (1960), Hindi cinema’s first songless talkie, Qatil puts in a few songs but unlike the original that attempted to include some socio-politico messaging this one tried to rely on the shock and awe of something that the audience already knew.

The thrust in B.R. Chopra’s Kanoon was on the notion that witnesses may be deceived and as a result, their false testimony could lead an innocent person to the gallows and Qatil, too, largely tries to make a case against the death penalty. There’s also an additional layer of whodunit within a whodunit. A law student, Kumar (Aditya Pancholi), is fueled by an argument over the death penalty between his father, the public prosecutor Sinha (Raza Murad) and a newspaper baron Mathur (Vikram Gokhale), who also happens to the father of his lover Kiran (Sangeeta Bijlani). In order to teach his father a lesson that an innocent could be wrongly implicated in a murder case, Kumar plants fake evidence that makes him look like the killer of a prostitute, Champa (Jamuna), mysteriously murdered a few days earlier. He then makes a video recording of the false evidence and his testimony with the help of his friend and journalist Anand (Shakti Kapoor). Kumar gets caught with the idea that when sentenced Anand would reveal the evidence at the right moment to save him. Everything plays out as planned – everyone’s convinced that Kumar’s the killer, but things go awry when Anand is killed and the evidence that could save Kumar destroyed. With nothing left that could prove his innocence Kumar along with Kiran and inspector Shyam (Kiran Kumar), who initially was convinced of his culpability, races against the clock to save himself.

More than the lackluster screenplay (Ravi Kapoor, Mohan Kaul) or even the predictable execution, the uninspired casting really does Qatil in. One’s not expecting much from a Sangeeta Bijlani for watching ice melt in real time would be a more fulfilling emotional experience than watching Ms. Bijalni act, but to cast Shakti Kapoor in the role of the savior is stretching the suspension of disbelief. What’s funnier is that the film lazily casts Kiran Kumar as a cop who looks bad but would turn out to be good by relying on his screen image post-Khudgarz (1987) and Tezaab (1988) but wants the audience to overlook Shakti Kapoor’s casting as Anand. The manner in which Kapoor’s character, Anand, dies with his body charred beyond recognition et al. pushes the film into the final act but the suggestion that Anand, too, harbored feelings for Kiran who picks Kumar over him early on in the narrative makes it abundantly clear that there’s some deeper mystery attached. With some other actor this McGuffin would have worked but with Shakti Kapoor, it is a lost cause.

Qatil’s screenplay could have included some subtle sub-plot about class disparity or some such keeping in mind the decade it was made in rather than attempting a straight thriller. But perhaps being his debut director Ashok Gaikwad decided to play it safe but in spite of the obvious shortcomings managed to instill a certain energy that only greenhorns manage. Gaikwad had learned the craft on films Chor Machaye Shor (1974), Inkaar (1977) and Andar Bahar (1984) and was a long time associate of Raj N. Sippy but could hardly stand out as an independent director. Largely recalled for anthropological reasons for being the filmmaker who launched Rani Mukherji’s career in Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat (1997), Gaikwad was busy through the 1990s and managed partial hits such as Doodh Ka Karz (1990) and Izzat (1991), his most noteworthy film where a parallel sub-plot of class and caste inequality elevates an otherwise bland narrative. Today, neither Ashok Gaikwad nor Qatil rings any bells but for what it’s worth it can be indulged for its steadfast campiness.

More than the lackluster screenplay (Ravi Kapoor, Mohan Kaul) or even the predictable execution, the uninspired casting really does Qatil in. One’s not expecting much from a Sangeeta Bijlani for watching ice melt in real time would be a more fulfilling emotional experience than watching Ms. Bijalni act, but to cast Shakti Kapoor in the role of the savior is stretching the suspension of disbelief. What’s funnier is that the film lazily casts Kiran Kumar as a cop who looks bad but would turn out to be good by relying on his screen image post-Khudgarz (1987) and Tezaab (1988) but wants the audience to overlook Shakti Kapoor’s casting as Anand. The manner in which Kapoor’s character, Anand, dies with his body charred beyond recognition et al. pushes the film into the final act but the suggestion that Anand, too, harbored feelings for Kiran who picks Kumar over him early on in the narrative makes it abundantly clear that there’s some deeper mystery attached. With some other actor this McGuffin would have worked but with Shakti Kapoor, it is a lost cause.

Qatil’s screenplay could have included some subtle sub-plot about class disparity or some such keeping in mind the decade it was made in rather than attempting a straight thriller. But perhaps being his debut director Ashok Gaikwad decided to play it safe but in spite of the obvious shortcomings managed to instill a certain energy that only greenhorns manage. Gaikwad had learned the craft on films Chor Machaye Shor (1974), Inkaar (1977) and Andar Bahar (1984) and was a long time associate of Raj N. Sippy but could hardly stand out as an independent director. Largely recalled for anthropological reasons for being the filmmaker who launched Rani Mukherji’s career in Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat (1997), Gaikwad was busy through the 1990s and managed partial hits such as Doodh Ka Karz (1990) and Izzat (1991), his most noteworthy film where a parallel sub-plot of class and caste inequality elevates an otherwise bland narrative. Today, neither Ashok Gaikwad nor Qatil rings any bells but for what it’s worth it can be indulged for its steadfast campiness.

More than the lackluster screenplay (Ravi Kapoor, Mohan Kaul) or even the predictable execution, the uninspired casting really does Qatil in. One’s not expecting much from a Sangeeta Bijlani for watching ice melt in real time would be a more fulfilling emotional experience than watching Ms. Bijalni act, but to cast Shakti Kapoor in the role of the savior is stretching the suspension of disbelief. What’s funnier is that the film lazily casts Kiran Kumar as a cop who looks bad but would turn out to be good by relying on his screen image post-Khudgarz (1987) and Tezaab (1988) but wants the audience to overlook Shakti Kapoor’s casting as Anand. The manner in which Kapoor’s character, Anand, dies with his body charred beyond recognition et al. pushes the film into the final act but the suggestion that Anand, too, harbored feelings for Kiran who picks Kumar over him early on in the narrative makes it abundantly clear that there’s some deeper mystery attached. With some other actor this McGuffin would have worked but with Shakti Kapoor, it is a lost cause.

Qatil’s screenplay could have included some subtle sub-plot about class disparity or some such keeping in mind the decade it was made in rather than attempting a straight thriller. But perhaps being his debut director Ashok Gaikwad decided to play it safe but in spite of the obvious shortcomings managed to instill a certain energy that only greenhorns manage. Gaikwad had learned the craft on films Chor Machaye Shor (1974), Inkaar (1977) and Andar Bahar (1984) and was a long time associate of Raj N. Sippy but could hardly stand out as an independent director. Largely recalled for anthropological reasons for being the filmmaker who launched Rani Mukherji’s career in Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat (1997), Gaikwad was busy through the 1990s and managed partial hits such as Doodh Ka Karz (1990) and Izzat (1991), his most noteworthy film where a parallel sub-plot of class and caste inequality elevates an otherwise bland narrative. Today, neither Ashok Gaikwad nor Qatil rings any bells but for what it’s worth it can be indulged for its steadfast campiness.

More than the lackluster screenplay (Ravi Kapoor, Mohan Kaul) or even the predictable execution, the uninspired casting really does Qatil in. One’s not expecting much from a Sangeeta Bijlani for watching ice melt in real time would be a more fulfilling emotional experience than watching Ms. Bijalni act, but to cast Shakti Kapoor in the role of the savior is stretching the suspension of disbelief. What’s funnier is that the film lazily casts Kiran Kumar as a cop who looks bad but would turn out to be good by relying on his screen image post-Khudgarz (1987) and Tezaab (1988) but wants the audience to overlook Shakti Kapoor’s casting as Anand. The manner in which Kapoor’s character, Anand, dies with his body charred beyond recognition et al. pushes the film into the final act but the suggestion that Anand, too, harbored feelings for Kiran who picks Kumar over him early on in the narrative makes it abundantly clear that there’s some deeper mystery attached. With some other actor this McGuffin would have worked but with Shakti Kapoor, it is a lost cause.

Qatil’s screenplay could have included some subtle sub-plot about class disparity or some such keeping in mind the decade it was made in rather than attempting a straight thriller. But perhaps being his debut director Ashok Gaikwad decided to play it safe but in spite of the obvious shortcomings managed to instill a certain energy that only greenhorns manage. Gaikwad had learned the craft on films Chor Machaye Shor (1974), Inkaar (1977) and Andar Bahar (1984) and was a long time associate of Raj N. Sippy but could hardly stand out as an independent director. Largely recalled for anthropological reasons for being the filmmaker who launched Rani Mukherji’s career in Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat (1997), Gaikwad was busy through the 1990s and managed partial hits such as Doodh Ka Karz (1990) and Izzat (1991), his most noteworthy film where a parallel sub-plot of class and caste inequality elevates an otherwise bland narrative. Today, neither Ashok Gaikwad nor Qatil rings any bells but for what it’s worth it can be indulged for its steadfast campiness.

- Gautam Chintamani is the author of the best-selling Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna (2014) and Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak – The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema (2016) | Tweet him – http://www.twitter.com/gchintamani

- http://osianama.com/indian-film-cinema-publicity-memorabilia/song-synopsis-booklets/qatil-1988-1108510?mastid=54671

View More