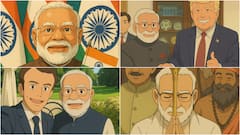

'New Crisis': Are Deepfakes Becoming A Threat To The Indian Legislation? Here's What Experts Are Saying

A recent surge of deepfakes has opened the door for public discourse. Minister of Information and Technology Ashwani Vaishnaw recently highlighted the need for legislation to address deepfakes.

As deepfakes of Indian actors like Alia Bhatt, Kajol, Rashmika Mandanna, and Katrina Kaif went viral on social media platforms, Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted the challenges posed by the technology at a public rally recently, calling it a "new crisis."

A comparison of the digitally altered video [L] and the original video [R]. (Source: Facebook/Screenshots/Modified by Logically Facts)

Deepfakes, as the name suggests, use a form of artificial intelligence (AI) called deep learning to make images of fake events or to replace one person's likeness convincingly with that of another. They are now being used for pornographic content, election propaganda, and spreading misleading narratives about ongoing events like the Israel-Hamas conflict. Their increasing sophistication makes detection difficult, enabling the rapid spread of disinformation.

A recent surge of deepfakes in India has opened the door for public discourse. Minister of Information and Technology Ashwani Vaishnaw recently highlighted the need for legislation to address deepfakes, while Minister of State Rajeev Chandrasekhar emphasized that existing laws are sufficient.

“All platforms and intermediaries have agreed that the current laws and rules, even as we discuss new laws and regulations, they provide for them to deal with deepfakes conclusively (sic),” Chandrasekhar said at the Digital India Dialogue session on November 24, 2023.

Logically Facts contacted experts to explore how significant a threat deepfakes pose and how effective the current legislation in India is to deal with the issue.

‘Anticipatory not reactive approach’

Earlier in November, Chandrasekhar had said, “For those who find themselves impacted by deepfakes, I strongly encourage you to file First Information Reports (FIRs) at your nearest police station and avail the remedies provided under the Information Technology (IT) rules, 2021.” He added that it’s a legal obligation for platforms to remove such content within 36 hours of receiving a report from a user or the government.

However, experts argue that the current approach is reactive. They suggest a cohesive anticipatory measure that could protect from the misuse of AI.

Speaking to Logically Facts, Lawyer and Executive Director of the Internet Freedom Foundation Apar Gupta said, “Filing complaints at a police station or through the online cybercrime coordination portal is looking at it from the perspective of a reactive application of the law for a certain kind of deepfake which is obscene. But what if it's not obscene? What if it's just a deepfake doing a small marginal thing? It is also casting the entire burden of enforcement on an individual victim now.”

Highlighting the risks associated with deepfakes, Gupta suggests looking at what other countries are considering.

For instance, regulation in the European Union, supported by the Digital Services Act, mandates a code signed by dozens of big tech signatories, including Google, Meta, and TikTok, to increase transparency. It requires social media companies to comply or potentially face a fine equivalent to six percent of their global turnover.

Suggesting a similar measure for India, Asia Policy Director at Access Now, Raman Chima, said, “India's not engaging in conversations, which means that we are actually starting from a very problematic approach where we're trying to create new legislation of our own without understanding the problem or even trying to make sure our laws are consistent with other democracies whom we depend on to have network effect on these platforms.”

He argues that the basic criminal tools to prosecute complaints exist, but what is required is something that “matches with the legal frameworks being adopted in other countries."

Chima says the sole onus of tackling the problem shouldn’t be on the platforms. “It's deeply problematic because why should Google and other platforms, that are not necessarily creating this content, automatically take it down without a legal regime? For example, I would be uncomfortable if someone created a parody video of a public figure, and then somehow, platforms automatically took it down without clear justification before the general elections,” he says.

On October 30, the White House passed an executive order establishing rules to minimize the risks associated with AI in the United States, including developing guidelines for content authentication and clearly watermarking AI-generated content. However, experts believe that bad-faith actors can circumvent this.

“Things like image markers are a soft commitment from companies, but we must also understand that only good users would use that signal anyway. Bad actors would always say, what's the point... they don't want it to be attributed to them,” says Microsoft’s director of product management Ashish Jaiman.

Emerging threats

A study by Sensity AI, a company tracking online deepfake videos, found that since December 2018, about 90 percent of deepfake videos are non-consensual porn, majorly targeting women.

In fact, a cursory Google search using relevant keywords shows that the top web searches of pornographic websites include the word ‘deepfake’ in their URL and feature prominently on such pages.

This despite the Indian government’s advisory to all social media and internet intermediaries to take strict action against deepfake images and videos, including that of Indian female celebrities.

“When the Mandanna incident happened, I looked online, and the top three hits on Google showed porn websites dedicated to deepfake technology,” Gupta said.

Screenshots of a post claiming that the woman seen in the video is Rashmika Mandanna. (Source: Facebook/Screenshots/Modified by Logically Facts.)

A report by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reiterates the proliferation of deepfakes in non-consensual pornography and adds examples from Russia and China to show how synthetic personas are being used to build credibility to promote regional issues.

“It’s going to get more tricky to identify them as the technology gets more sophisticated,” according to Gupta. “And when you think about it much more broadly, such technologies can be useful for sectarian purposes to show minorities in an unflattering light. It will be used for communal purposes. It will be used in politics to show politicians doing or saying things they never did. It's already a problem and will deeply impact human trust,” he added.

A September 2023 report by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security highlights how the scale of media manipulation has dramatically increased over the years. And as the lines between what is real and what is synthetic get blurred, Jaiman said good actors need to watch out for the liar’s dividend – where an actual bad act or event is discounted as a deepfake.

Citing the example of the former U.S. President Donald Trump calling his tape denigrating women as “fake,” the expert said, “bad actors can use this moniker to hide behind their bad acts.”

Jaiman quips that even if tech platforms adopt stricter measures to curb the spread of synthetic content, closed platforms like Telegram have multiple channels and bots dedicated to providing a paid-for deepfake service, adding “technology enables you to not only create something harmful, but you can actually make it very personalized.”

The way forward

Chima says that rather than outsourcing the problem to the private sector and holding platforms responsible, the Indian government should first engage with developers of such tools, and understand how it can impact everyday people.

“You need to find out what everyday people or people in vulnerable communities might be encountering, and that's not that's not what's happening. Instead, we’re seeing a rush to potentially legislate because known film actors or political figures are being targeted,” he said.

Gupta suggests an approach where the government works in tandem with domain experts – from academia, civil society, and human rights – to measure the social impact of artificial intelligence.

“I think such a body needs to be there because the impact of AI-based technologies will be massive across sectors in India. What we need is beyond the blunt force of censorship resulting in content takedowns... we need heuristic policy-making,” he opines.

But not all deepfakes are made for malicious purposes. They are also popularly used for satire, art, and branding, making it difficult to ascertain intent.

Gupta says judging intent is a secondary determination, but consumption of increasingly convincing synthetic content of individuals being depicted in a certain light, or saying something can cause profound damage. “We are all taught in media literacy to look behind the curtain and question our own biases, but that’s often a high cognitive burden to place on people. It impacts social trust, in which people are naturally attuned to believe what they see. A very clear, crisp 4K video of me saying something I never did is essentially going to damage a person's ability to trust things they see,” he said.

(Edited by Nitish Rampal)

This report first appeared on logicallyfacts.com, and has been republished on ABP Live as part of a special arrangement. Apart from the headline, no changes have been made in the report by ABP Live.

Related Video

Apple creates a new record in iPhone sales after launch of iPhone 16 | ABP Paisa Live

Top Headlines