Curious Case Of Rs 1000 Electoral Bonds Purchased By Big Corporate Donors Like ITC

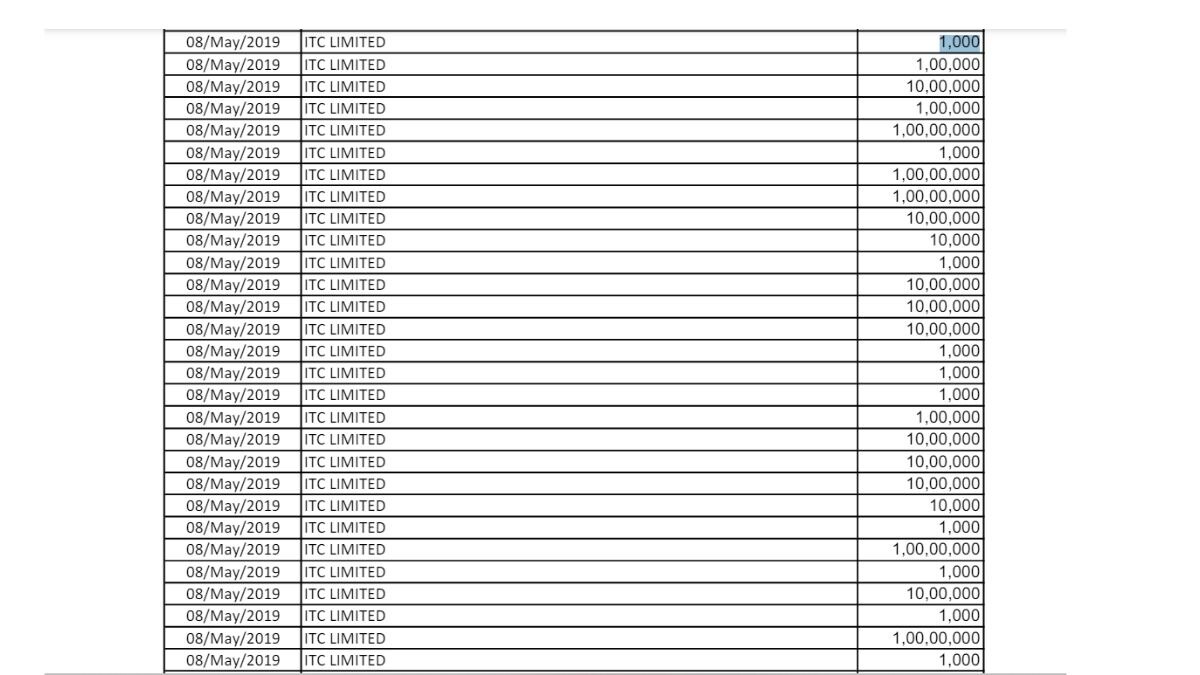

Electoral Bonds Data shows Indian conglomerate ITC purchased 15 electoral bonds worth Rs 1000 on the same date it purchased several bonds worth Rs 10,000, Rs 1,00,000, Rs 10,00,000, and Rs 1,00,00,000

A quick scan of the donors to the Electoral Bonds Scheme shows that big corporations and high net-worth donors bought not only electoral bonds of higher denominations of 1 crores or Rs 10 lakhs but they also bought bonds worth Rs 1000, Rs 10,000 which were perceived to be a route for donation by people not belonging to the wealthier backgrounds.

Justice Sanjiv Khanna's opinion in the Supreme Court judgment on Electoral Bonds said that the data submitted in the Supreme Court on the Electoral Bonds Scheme suggests that around 94% of electoral bonds purchased since the scheme was launched in value terms were found to be for Rs.1 crore which suggests that corporates or individuals with high networth were main donors in the electoral bonds scheme.

“Data show that more than 50% of the bonds in number, and 94% of the bonds in value terms were for Rs 1 crore. This is indicative of the quantum of corporate funding through the anonymous bonds,” the judge noted.

But, the latest list on the donations made to political parties available on Election Commission Of India's (ECI) website has unveiled another side to this story. The quantum of corporate funding is much more as these big donors also bought bonds worth Rs 1000, Rs 10,000, Rs 100,000, and Rs 10,00,000.

For instance, the Indian conglomerate and FMCG giant ITC purchased 15 electoral bonds worth Rs 1000 on the same date it purchased several bonds worth Rs 10,000, Rs 1,00,000, Rs 10,00,000, and Rs 1,00,00,000. (See List Below)

The question here is that why would these bond purchasers who can very well buy bonds in higher denominations split up their donation in small as well as big amounts.

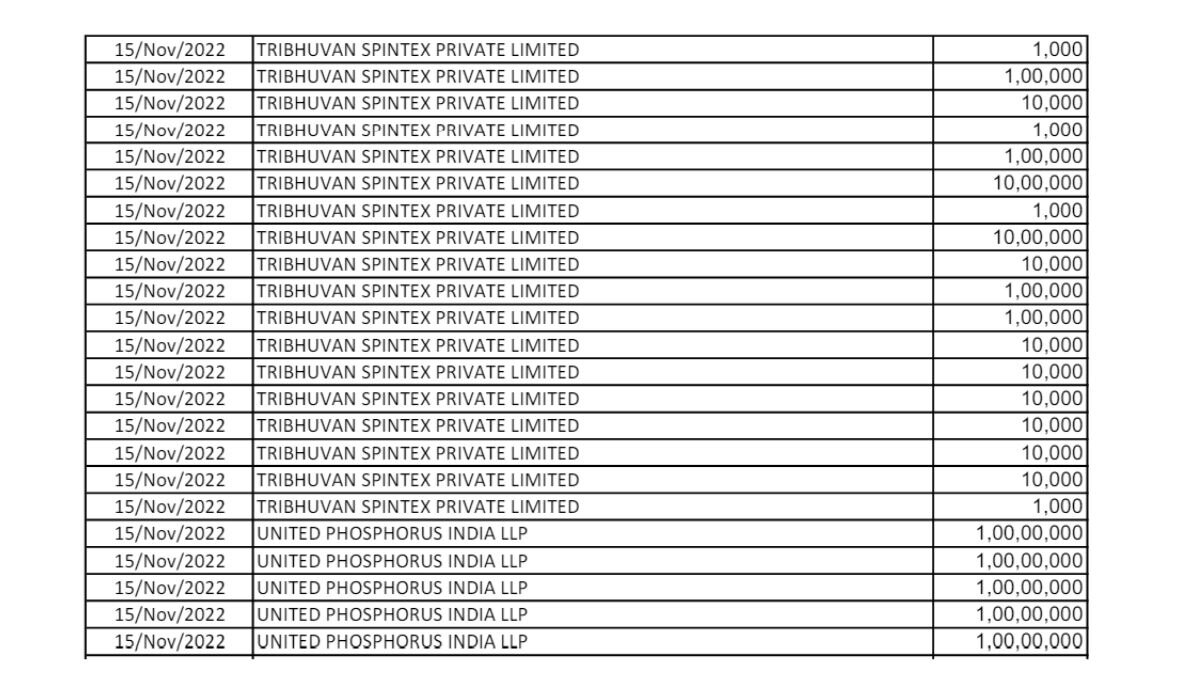

This is not a singular instance. Many big donors have made donations on the same date by purchasing these electoral bonds in different denominations. However, what is less common on the list are single donors and individuals purchasing bonds in lower denominations. Another example is of Tribhuvan Spintex Private Limited (TSPL) cotton yarn manufacturer with a spinning plant that is situated near Rajkot, Gujarat (See List below).

The Electoral bonds were introduced as interest-free money instruments or bearer bonds that could be purchased by companies as well as individuals in India from branches of the State Bank of India (SBI). These were anonymous instruments by which a person or a company could donate to a political party as the name and other information of the donor were not entered on the instrument.

They were sold in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore. To purchase them, one had to have a KYC-compliant account. The political parties had to encash the donation within a specified time. There was no limit on the number of electoral bonds that a person or company could purchase.

The scheme was introduced by the government through amendments to four Acts by the Finance Act of 2016 and 2017.

The four Act amended by the government were-- Representation of the People Act, 1951, (RPA), the Companies Act, 2013, the Income Tax Act, 1961, and the Foreign Contributions Regulation Act, 2010 (FCRA).

Before the scheme was implemented the political parties were required to declare all donations above Rs 20,000. There was also a check on corporate donations as companies were not allowed to make donations amounting to more than 7.5% of their total profit or 10% of revenue.

It was argued in the Supreme Court that the scheme treats common man differently from big corporations as it gave anonymity to corporate donors but citizens who were donating Rs 2000 in cash were asked to disclose their names.

On Februrary 15, in a landmark judgment the Supreme Court's five-judge Constitution Bench unanimously held that the Electoral Bond Scheme is unconstitutional and violates Article 19 (1) (a) of Indian Constitution. The court gave two opinions, one by Chief Justice Of India DY Chandrachud and another by Justice Sanjiv Khanna. However, both arrived at the same conclusions.

While reading the verdict the CJI said that the petitioners had raised two primary issues-- Firstly, whether amendments are violative of right to information under Article 19(1)(a). And secondly, if unlimited corporate funding violates principles of free and fair elections.

On these contentions the top court held that the anonymous electoral bonds are violative of right to information under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution.

The court further held that the scheme could lead to quid pro quo arrangements between political parties and corporates. The petitioners had contended that corporates could use the Electoral Bond scheme for backdoor lobbying to get a favourable policy from the ruling party.

The Centre had contended that the electoral bond scheme was brought in to curb black money in the system.

Related Video

Vande Bharat: India’s First Vande Bharat Sleeper Train to Run Between Guwahati and Kolkata